I was running a training day In Bradford yesterday and to find my way to the school, as usual, I obediently followed my phone sat nav. I noted as I was getting close that I was passing through Saltaire and there was one of those brown heritage signs that pointed in the direction of Salts Mill. Normally I have to dash home after a workshop but there was no rush today so I decided I’d pay a visit if I had enough energy left after a full-on day training. The workshop proved to be the best of the year so buoyed by that I followed that brown sign.

First impressions were great – trendy shops and stunning architecture. Total fluke but I like the way the railings follow the lines of the building.

Here’s some background to the town:

Saltaire is Sir Titus Salt’s factory town. Founded in 1851, the village is located roughly a dozen miles to the west and north of Leeds. Like many of the British World Heritage sites, Saltaire’s preservation celebrates Britain’s industrial past.

Though the Industrial Revolution transformed Great Britain and the world, it often came with poor working conditions and a hard life for the workers. Salt envisioned a factory town that would provide a better life for his workers. And thus the well-planned factory town of Saltaire with its embedded social services was created.Salt built neat stone houses for his workers, wash-houses with tap water, bath-houses, a hospital, and an institute for recreation and education that included a library, a reading room, a concert hall, billiard room, science laboratory, and gym.

The village included a school for the children of the workers, almshouses, and a park. Saltaire, in its time, was a comparative workers utopia. It is viewed today as an important development in the history of 19th century urban planning.The textile mill in Saltaire produced goods until 1986. Today the factory and town remain largely intact; UNESCO World Heritage status protects the area from the hammers of redevelopment.

Though the factory’s buildings have been repurposed and now serve other functions, the exteriors remain much as it has been. Beyond the factory the well-planned grid of workers’ homes interspersed with community buildings still climbs up the hill from the factory.

The Leeds Liverpool canal runs through the town – now pleasure boats go up and down but I tried to imagine what it must have been like at the height of the industrial revolution.

When Titus Salt, a devoted member of the Congregational church, commenced the design and construction of his model village at Saltaire, a Congregational church was the first public building commissioned. Salt donated the land and paid for the cost of the church himself, a cost of £16,000 (equivalent to £1,622,091 in 2019).

The church was designed, as was the rest of Saltaire, by the Bradford-based architect partnership of Lockwood and Mawson in the Italianate Classical style. Local firms were used for the works. The firm of John Ives did the woodwork and carvings while Moulton Brothers undertook the masonry work.

Since 1972 the church has been known as Saltaire United Reformed Church following the merger of Congregational Church in England and Wales and the Presbyterian Church of England.

The allotments were interesting – right next to the canal.

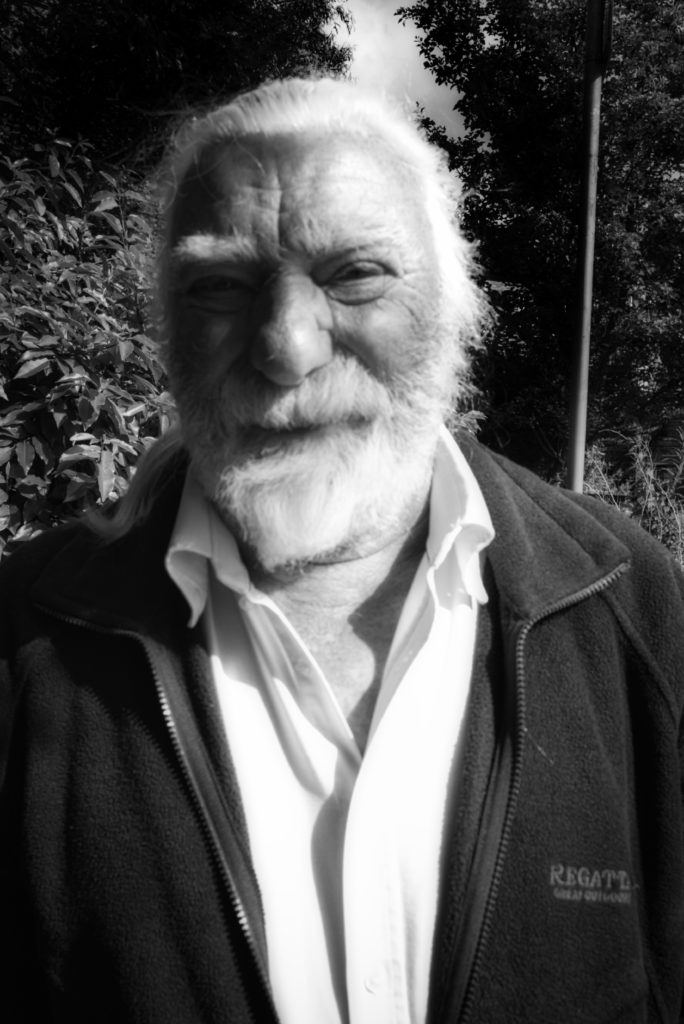

I had a nice chat with the gentleman who was an allotment holder. He said they’d lost a few plots to Shipley College who have a building in the town – apparently the TV gardener Alan Titchmarsh is an alumni, there’s also a badger that lives there.

An old fashioned electrical repair shop caught my eye as I made my way back to the car park.